“Ma, I Saw an Amorsolo By The Shoe Rack”: A Discussion of National Artist Works in Private Hands

By Ellysse Nadine Calma

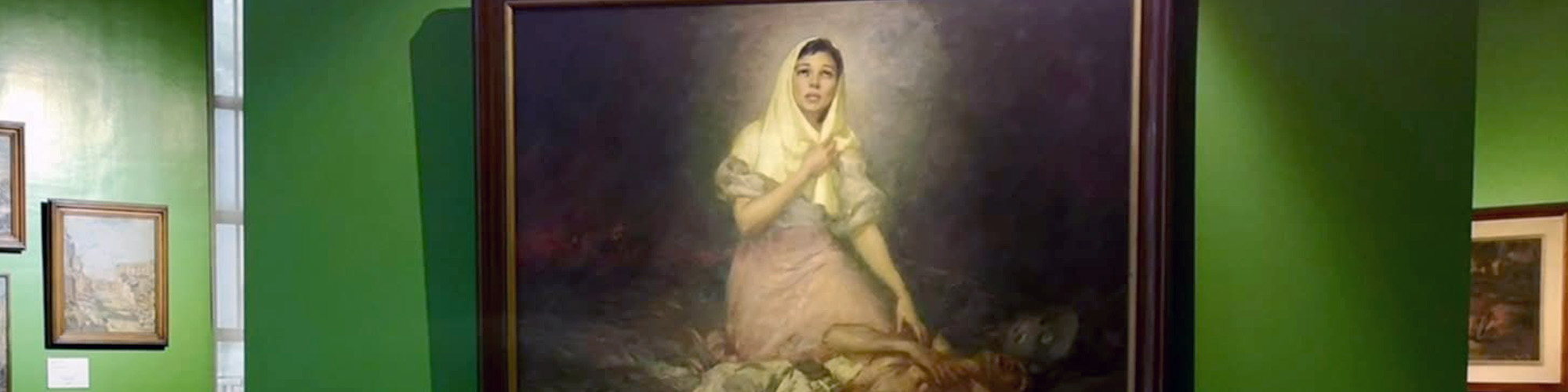

There it was—Lady with Umbrella, hanging on a gilded gold frame right by the doorway, looking like a proclamation of prestige, wealth, and culture that she could own one in her own home. At first, it was so disarming—how could you expect that that would be the first piece hanging by the door?

“Tita Rachel! So nice to meet you!” I squeaked, coming in close for a hug craning my neck over to glance at the portrait sitting by her shoe rack—still so shellshocked that I could see a piece from this artist so close to me.

I entered her apartment, all filled with beautiful paintings and ceramics, many of which were by national artists. To my left was an Arturo Luz, to my right an Ang Kiukok, and right by the doorway, the Amorsolo. I could not believe that I was surrounded by paintings that had been, all my life, just a part of textbooks and online photos. Here, these paintings and I breathed the same air, separated only by how socially acceptable it was to put my face close to them.

National artists have always held that air of prestige and formality. For many, even I, could never in their wildest dreams imagine that they could come so close to such a painting, let alone see each crack of oil and stroke. These paintings stand as monoliths in the zeitgeist, understood as never to be viewed unless behind the velvet rope at museums. But here, in the private home of one woman, this veiled beauty was unraveled before my eyes. All these works, made and crafted by artists who, by the very law, are considered representations of the Filipino collective consciousness. Not only could I see them unbarred, I saw them in conjunction with everyday household items—the Arturo Luz as seated with the dining table as a backdrop to lunch conversations; the Ang Kiukok moving with you as you traverse down the hallways to the bedroom; and the Amorsolo standing proudly as you remove your shoes to enter the home. All of these nationally proclaimed art pieces served as merely decorative in her home, a stark contrast to the art museum which displays these pieces as sacrosanct, stand-alone creatures gatekept by admission tickets.

These growing movements in the collection of private art beg the question: Does art fare better when kept in the hands of the wealthy few? From my experience, I know Tita Rachel does her due diligence in the collection of these pieces—being wealthy enough to hire curators and art experts, and keeping these masterpieces in temperature-controlled environments in her home, I’m guessing. But who can say the same for the thousands of compositions stuck in public museums across the country, who are subject to the whims of government budgeting, hot weather, and the overly curious public who touch their aged faces?

For national artists in particular, whose work is believed to have not only moved our cultural scene forward through their contributions, but has also continued to represent our artistic lenses inwardly towards ourselves, and outwardly on a global scale, we are faced with a major dilemma: Do we continue to let private collectors shift hands and pass the beauty only amongst themselves?

Art fairs, open to the public, exist then as a liminal space—a bridge between both worlds: allowing us to peer into the world of art in a space so common to us and yet are able to be preserved, passed down, purchased, and loved by those who are willing and can afford to do so. We open the invitation to many who, often, do not have access to a museum to experience art for what it is in spaces that often serve as middle grounds. This is something Tubô Cebu Art Fair does differently—at Tubô, there is no velvet rope. Situated in the middle of one of the busiest mall hubs in Cebu City, Tubô positions itself uniquely as truly the liminal space that was born out of a desire for art to emerge and break through to the everyday. Here, the art exists in the same air as the fastfood joint down the hallway, and even the public restroom further down, and it is here where we peek behind the gilded frame and introduce ourselves into the world behind the canvas.

Art exists as woven into the spaces we frequent. But the nature of art fairs are usually meant to be profitable—after all, the process of making art is difficult, so it warrants its monetary expense. Does this mean then that these spaces, even Tubô who positions itself as an affordable art fair, only exist for those who can afford it? Or conversely, do these spaces hold a larger meaning? To break the fabric of the monolithic art world into the world-of-our-own? Where do we hold the line of public access to private hands? How do we even start the conversation?

Ultimately, we return to the nature of art itself—it is to be seen. It is truly a liberating experience to view these pieces firsthand. It challenges your sense of self—shifting your perspective whenever you can view different styles and forms of it, whether it be contemporary art, film, theater, or music, speaking to its very importance.

In that moment, staring deeply into the eyes of the Amorsolo, staring so close that I could see flecks of dust dance in the air of the overhead display light, I was reminded of how many times I walked past art galleries in malls. I remembered how those spaces, broken up by glass and doors physically barring me from entry—asking myself that even if these spaces are free to enter, am I even welcome to step inside?

I smiled softly to myself as I snapped a photo for my mom, thinking to myself how much she would love to see this for herself. Lady With Umbrella smiled back at me on my phone screen. It was just me and her lovingly staring at each other by the shoe rack—and in that moment, I was so glad to have met her.

*Names have been changed to protect their identity.